Features

You are here

The disability movement: a brief history

July 3, 2013

The disability movement has a long history that is largely unknown to most activists. A huge part of the disability rights legacy has been made invisible by the more socially acceptable, liberal vein of human rights advocacy entrenched in modern disability politics and policies. The connections between the disability movement and workers movement are known to even fewer people, but that is where the movement was born.

Capitalism and disability

Though the history of the disability movement is new to many of us, the social condition of disability is not new to capitalism. Through capitalism, disablement is imposed upon people whose bodies and minds do not conform. This label has long been used and re-used to oppress people, confining them physically, socially, and economically. To put it in terms of the Occupy movement; they are often the lowest 1% of the 99%.

Industrial capitalism imposed the label of disablement upon those people who did not conform to the standard of the ideal worker. A primary source of oppression of people with disabilities (those who could work with a reasonable accommodation) is their exclusion from capitalist exploitation. It is important to remember that the concept of disablement had to be devised by the capitalist system in order to exclude other means of production from the workforce. Allowing such flexibility to workers has the potential to undermine capitalism and allow the possibility of alternative systems to take its place.

Early movement

In the UK, years of explosive strikes, and growth in trade unions, also saw the formation of the British Deaf Association and the National League of the Blind and Disabled (NLBD). Founded as a trade union in 1899, the NLBD joined forces with the Trades Union Congress three years later. Its members included blind war veterans, mainly working in sheltered workshops, who campaigned for better working conditions and state pensions. The league organized a national march of blind people on Trafalgar Square in 1920, carrying banners with the slogan ”Rights Not Charity”. Despite its small numbers, the demands of the march were widely supported. The first legislation specifically for people who are visually impaired was passed in the same year, followed by more in 1938.

The long economic boom in the years that followed created space to challenge institutionalization and the patronage of charities, and an increasing number of people with disabilities were joining the workforce. By the 1960s some had begun to reject their labeling by the professions as deviants or patients, and to speak out against discrimination. Inspired by the civil rights struggle, the disability movement began in the US and Canada.

Modern movement

An example of this shift was the “Rolling Quads”, a group of student wheelchair users at the University of California, who established the first Independent Living Centre in 1971. This sparked what became known as the Independent Living Movement, and within a few years hundreds of Independent Living Centres were created across the US and in countries like Britain, Canada and Brazil. Its opposition to institutionalization, and focus on the self-reliance of people with disabilities gave the independent living movement a lasting influence. According to these organizers, oppression was mainly caused by physical barriers to the environment, and without these physical barriers they would be considered equal in society.

Independent Living Movement organizers argued that paying exclusive attention to the problems of personal impairment failed take into account the bias and discrimination experienced by people with disabilities in employment, health, education, housing, transportation, public policy and social and community services.

Despite these shifts, ableist practices still exist within the capitalist economic system: the impairment presented by people with disabilities is seen as an added cost. These perceived expenses are often “compensated” by paying less wages to workers with disabilities. This can be seen in employment programs throughout Toronto and Canada that are supposedly designed for people with disabilities; in reality these programs serve as a source of cheap labour. They also serve to remind people that their worth in a capitalist economy has much more to do with their perceived labour power than actual skills or education.

Fault lines

Much of the work that was done in the past was influenced by Marxism, but the organizers were mainly white men, and most of them only had physical disabilities. Despite their influences, these early organizers did not directly challenge the capitalist ideal of workers, and instead sought ways for people with disabilities to conform to that ideal.

Because of that history, many people continue to see the disability movement as paternalistic; women do much of the work to move forward, but white men are still the most common face of the disability movement. We know now that the oppression of people with disabilities is far more complex than physical barriers, and like many movements the disability movement has been working to incorporate the struggles of other movements in order to grow.

The movement also suffers from a generational gap. Previous generations that fought against institutionalization and non-existent accessibility are only beginning to reach out to the younger generation of people with disabilities. This younger generation is at times less aware of the fact that others fought for the accessibility that they now enjoy. Some within that group are now beginning to realize that in order to create real change, we have to stop trying to work exclusively within the systems that oppressed us in the first place.

Solidarity

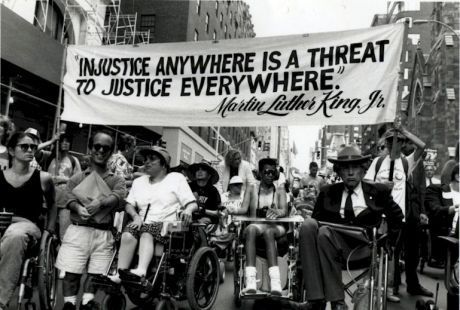

In some ways people with disabilities are key to revolutionizing the way we value the contributions people make to society, and continue to build solidarity across movements. We need to educate each other about the past struggles of the disability movement, and how those moments of solidarity have shaped the world we live in today.

So how can socialists build solidarity? The best thing we can do right now is build connections. Reach out to people with disabilities that we see doing activist work, and connect them with related struggles. For too long, the rights and oppression of people with disabilities have been discussed behind closed doors, or not at all, but through actions like the Toronto Disability Pride March we find our voice, and make ourselves heard in the chorus of movements.

The third annual Toronto Disability Pride March is October 5, 2013.

Section: