What we think

You are here

Climate Crisis Accelerating – Radical Action Required

December 22, 2018

Dire warnings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released last month have reignited debates over who is to blame for the climate crisis, and what kind of action is required to stop it in time.

The world’s leading climate scientists warn we have just twelve years to limit global warming to 1.5C. If we fail to do so, hundreds of millions more people will face significantly worse impacts from droughts, floods, extreme heat and poverty with each half degree increase above that goal. Many of the contributing scientists see this report as extremely conservative in its projections, making no mention of climate refugees or tipping points which could dramatically accelerate the crisis.

The gap between these warnings and the current state of international climate politics could not be starker. With existing commitments, the world’s governments have set us on track for a world that’s 3 degrees hotter; threatening the existence of civilization as we know it. Donald Trump has vowed to walk away from the Paris accords altogether, and newly elected Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro is promising to open the Amazon for unfettered development. According to a newly released study, Canada is one of the worst climate criminals, whose policies would put the world on track for 5C warming if other countries followed its example.

In this context two related “solutions” have come into focus, carbon pricing and personal lifestyle changes. The first part of this two-part series will address the problem with using personal lifestyle choices as a political strategy. The second will address the problem with carbon pricing policy that relies on market forces to bring about a transition off fossil fuels.

The central problem with these approaches is that they allow the 1% and their corporations to avoid taking direct responsibility for the climate crisis. Instead these policies place the burden on the backs of working-class people, especially the oppressed and marginalized groups that make up the majority of the working class. This strategy also undermines efforts to mobilize the working class to demand action on climate change, and provides an opening for right-wing politicians like Doug Ford and Andrew Scheer to whip up opposition to any form of climate action.

The working class must be central to any strategy for fighting climate change because rising emissions stem directly from the capitalist exploitation of workers, their communities, and the natural world they are a part of.

Real action on climate change means working people acting collectively to take the power away from corporations and the market and put it in the hands of the people most impacted. We can’t leave that power in the hands of well-meaning technocrats to create policies and reforms that depend on the very “free” market system that is causing the problem. Neither can we look to individual consumer strategies, these serve to reinforce our atomization as individual consumers and thus undermine the potential for collective action. Systemic change can only come from the mass mobilization and unity of workers and their communities. It also means mobilizing in solidarity with indigenous sovereignty struggles that are driving the movement against pipelines and other Tar Sands projects.

Eat the rich, save the planet

One of the most prevalent responses to the IPCC’s report in the mainstream media is to focus on what individual consumers can do by changing their personal habits. CNN tweeted, “Scared by the new report on climate change? Here’s what you can do to help: Eat less meat – Swap your car or plane ride for a bus or train – Use a smart thermostat in your home.” Most of these stories reassure readers that they JUST have to do their part as responsible consumers. There is rarely any mention of corporations or discussion of how to get involved in collective political action.

Fortunately, a growing number of people are rejecting this narrative that ignores the role of major corporations while admonishing individual consumers to “do their part”. As one keen follower tweeted back to CNN, “reminder that 100 corporations are responsible for 71% of global greenhouse gas emissions and presenting the crisis as a moral failing on the part of individuals without noting this fact is journalistic malpractice.” Last month, GQ featured an article titled “Billionaires are the leading cause of climate change” and on Vox “The best way to reduce your personal carbon emissions – don’t be rich”. Eat the rich memes are also being widely shared on social media. This comes as a welcome shift after more than two decades of conventional thinking in the mainstream environmental movement.

Many climate activists see no contradiction between emphasizing the importance of individual consumer choices and efforts to mobilize ordinary people to stop climate change, but most socialists see that differently.

This doesn’t mean socialists object to advocating any choices as consumers that might have some political significance. In some cases, these choices are made as part of a boycott or other campaign in solidarity with striking workers or to support other struggles. No one should fault working-class people who try to make personal consumption choices consistent with reducing their carbon footprint. These kinds of choices often affirm our own resistance to a system of consumption that has largely been forced on us. It’s one small way of sticking it to “the man” in a system where the power and influence of major corporations and wealthy elites means their choices far outweigh our own. In other words, these choices have a symbolic value greater than their actual impact on the planet.

Moralizing about lifestyle undermines collective action

The problem comes when some in the climate justice movement try to raise these small decisions to the level of a political strategy, turning specific choices made in solidarity with specific struggles into far reaching lifestyle changes. This strategy ends up focusing us inward on our own lives, isolating us as individuals, rather than turning us outwards to mass collective action and connecting us with our fellow workers to challenge the system. This focus on lifestyle moralizing ends up reinforcing the broader neoliberal culture of hyper-individualism and mass consumption rather than rejecting it.

As the Guardian’s Martin Lukacs argues in a 2017 column titled “Neoliberalism has conned us into fighting climate change as individuals”:

“Even before the advent of neoliberalism, the capitalist economy had thrived on people believing that being afflicted by the structural problems of an exploitative system – poverty, joblessness, poor health, lack of fulfillment – was in fact a personal deficiency.

Neoliberalism has taken this internalized self-blame and turbocharged it. It tells you that you should not merely feel guilt and shame if you can’t secure a good job, are deep in debt, and are too stressed or overworked for time with friends. You are now also responsible for bearing the burden of potential ecological collapse.”

Taken in this context, it shouldn’t be surprising that many working-class people instinctively object to being moralized at like this. Rejecting, defying and even mocking those who push for vegan diets and other kinds of green consumption becomes an understandable act of resistance, even if people doing the moralizing often have the best of intentions.

Capitalism forces us to overconsume

The reality is that most working-class people aren’t given a choice about their consumption. We might be able to make a few choices to support a particular cause or to ease our cognitive dissonance, but we can’t escape the broader culture of overconsumption. It’s built into the production and distribution of everything we consume, and the reality of how we’re forced to live our lives.

To take just one example, rapidly rising rents and housing prices mean working-class families are forced to move out to suburbs far from work. These suburbs often have little or no real public or mass transit option available; they are developed in such a way that accessing everything from shopping to services requires a car to get around, especially if you have kids. This trend is one of the reasons emissions from the transportation sector in Canada have risen 42% since 1990 to become the largest source of emissions, after oil and gas, in spite of increasing fuel efficiency and rising gas prices.

Globalization means that there are more emissions embodied in everything we consume. Production of most manufactured goods has shifted offshore to developing nations as corporations move operations to where they can profit the most from cheap labour and where carbon intensity (emissions per unit of production) also tends to be the highest. The resulting four-fold increase in global trade since 1990 and associated shipping and transport also means dramatically higher emissions. One study cited in Andreas Malm’s essay, “China As Chimney of the World” (found in his book “Fossil Capital”), estimated that between 2002 and 2008 fully 48% of China’s emissions stemmed directly from its export sector. This doesn’t include the significant emissions generated by building the infrastructure to accommodate this trade. Meanwhile, Canada’s trade deficit with China increased six-fold between 2001 and 2016.

As Malm argues, in developed countries “The carbon foot-print of a smart, tech-savvy, happy-go-lucky art director is not a function of what he produces, but of what he consumes, much of which will be imported from nations still doing the dirty work of manufacturing…The lightness of the MacBook air crowd is an illusion grounded in myopia.” He argues further that western workers are far from being to blame for rising emissions; they are the most likely to have resisted this process because they are often the victims of it.

Lastly, time is a precious commodity for most working-class families. Long days and weeks at work, combined with long commutes, childcare and housework, force us to seek out convenience wherever we can find it, even if it negatively impacts our health and the ecosystem we depend upon. Often this means driving, eating out or eating packaged and processed foods, and buying whatever is readily available without having the time to find out where or how it’s made.

For activists, this also forces us to make a choice about what we do with the time that we have and with the limited opportunities we find to talk with coworkers, classmates etc. This too becomes a choice between focusing on personal consumption and lifestyle or focusing on collective action.

In contrast to the messages of artificial overconsumption, or rather because of it, most working-class people are having a hard time consuming everything they need. Real wages are falling, precarity is increasing and costs for everything are going up. We are already making hard choices every month, robbing Peter to pay Paul, trying to keep up with our debt payments, paying whatever bills we can afford to pay to keep the lights and heat on and a roof over our and our children’s heads. In this context it is a luxury to be able to choose more expensive green alternatives.

Eat the rich?

A 2017 study from researchers in British Columbia and Sweden shows that the consumer choices with the greatest impact on individual carbon footprints are also those that are the least accessible or affordable for the average working-class person.Their top three suggestions are having fewer children, living car free, and avoiding one round trip transatlantic flight.

Setting aside their absurd assumption that parents should be responsible for the future emissions of the children, the rest of the study shows that only the rich can truly afford to live a carbon reduced lifestyle. Going car free is only really a choice for those who can afford to live in urban cores with better public transit and who have work, shopping and services nearby. Most of us would leap at the chance to take a transatlantic flight, if we could afford it, and purchasing green energy is only a choice for homeowners with the extra cash to pay for solar panel installation. Choices that are accessible, like changing lightbulbs or recycling, have far less impact. So, it is the rich, not the poor, who have the greatest power to effect change through their consumption choices and yet they are the least likely to do so, often seeing their own excess and immunity to its consequences as a confirmation of their wealth and status.

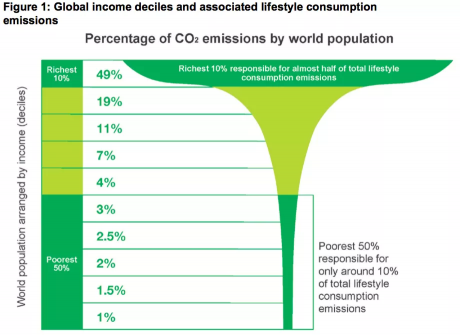

The poor and the working class have the least power to effect change through their consumption and are also the least to blame for emissions from lifestyle. A 2015 Oxfam media briefing directed at governments participating in the Paris Climate Talks points to the inextricable link between inequality and climate change. Titled “Extreme Carbon Inequality” the briefing shows that the wealthiest 10% of people in the world are responsible for 50% of emissions while the poorest 50% are responsible for just 10%. This holds true both between poor and rich nations as well as between the rich and poor of individual countries, including the wealthiest nations of the G20.

The report also underscores the fact that those least responsible for the climate crisis are also most likely to be its first victims:

“A recent study by the World Bank found that in the 52 countries analysed, most people live in countries where poor people (defined as the poorest 20% of the national population) are more exposed to disasters like droughts, floods and heat waves than the average of the population as a whole – and significantly so in many countries in Africa and South East Asia.”

This disparity can also be found within rich countries as well:

“When Superstorm Sandy hit New York in 2012, 33% of individuals in the storm surge area lived in government-assisted housing, with half of the 40,000 public housing residents of the city displaced.”

It turns out that eating the rich (#ethicalcannibalism) is the most rational and impactful of all the lifestyle choices we could make. But instead of forcing ourselves to eat a Trump burger, a far more palatable strategy is to build on the key struggles that working-class and oppressed people are already waging. Building the collective power of working people is essential to challenging capitalism’s fossil fuel economy, and these struggles are often directly related to reducing emissions and tackling climate change.

The lack of affordable housing is a direct contributor to rising emissions. Thus, working class renters in Vancouver and Toronto fighting for affordable housing are also fighting for a vital climate solution. Arguing the urgent need for affordable housing to help reduce emissions only serves to broaden the movement for affordable housing, while at the same time strengthening the climate justice movement.

Socialists have a vital role to play in connecting these movements and showing that they are part of the fight against this system that exploits both workers and the planet for profit while forcing the working class, the poor and the oppressed to bear the impacts of ecological destruction. To act on this, we need to be clear that workers are the victims rather than the cause of this crisis and that they are also the key to its solution.

Section: