Features

You are here

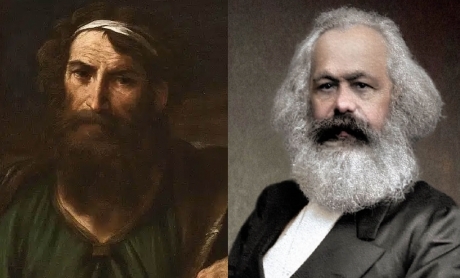

Review: Breaking the Bonds of Fate - Epicurus and Marx

February 11, 2026

Review of Breaking the Bonds of Fate: Epicurus and Marx

by: John Bellamy Foster

We live in times of a deepening interconnected global crises: rising inequality, authoritarianism, fascism, and inter-imperialist rivalry conditioned by climate and ecological catastrophes that threaten life as we know it on planet Earth.

Given this, one might ask; why should we care about Marx’s engagement with the ideas of the ancient Greek philosophy of Epicurus?

In Breaking the Bonds of Fate, John Bellamy Foster shows that Epicureanism had a profound influence on Marx and Engels. Foster’s earlier book, Marx’s Ecology, shone a light on Marx’s ecological critique of capitalist production, and touched on Epicurus’s influence. Now he shows how key elements of Marxism were prefigured by Epicurus thousands of years earlier. Since various strands of Marxism have denied or distorted this influence – and the bedrock of the dialectic in nature on which historical materialism stands – it does matter in these tumultuous times.

While some knowledge of philosophical frameworks is assumed in the work, it is largely written in an accessible style that most readers will be able to navigate.

Foster starts by situating Epicurus in his time. He was the son of colonists of the island of Samos in the Aegean Sea, which had been seized by Athenian forces from the Persian empire. Shortly after his birth, Alexander the Great of Macedonia incorporated Athens into his empire, though allowing relative autonomy for the city-state. At about the time of Epicurus’s mandatory military service, Alexander died, leading to “an ‘empire of chaos’ during the Wars of the Diadochi (or Successors) of the Macedonian Empire”.

After studying the philosophy of the Pre-Socratics, Plato and Aristotle, Epicurus set up schools, first in Lampsacus (in modern day Turkey), then later in Athens.

Other philosophical schools in the city used public space for lectures and attracted young, well educated, aristocratic Greek men. His critique of the ruling classes that dominated these schools that “Nothing is enough for those for whom enough is too little” is as applicable today as in his age.

His school, in contrast, was comprised of the private spaces of a house and a non-contiguous garden just outside the city walls, that welcomed “the uneducated as well as the educated, embracing slaves, paupers, craftsmen, country folk, and woman.” Greeks and “barbarians” were welcomed alike, accounting for Epicureanism’s spread eastward. Rather than top down instruction, “The Garden” – as his school was known – fostered open discussion and encouraged critical thought. It was also literally a “kitchen garden (Kepos) of the kind used for growing beans, cabbages, turnips, radishes, lettuce, beets, coriander, onions, dill, cress, cucumbers, basil, and savory. It provided food for communal meals and a modicum of self-sufficiency.”

It was a sanctuary from the mortal dangers for people espousing radical ideas, where a community of equals based on unity and friendship through a “social compact” could thrive, enjoying the simple pleasures of life and the contentment (ataraxia) of having enough. Indeed, for Epicurus, “the world is my friend.”

Very few of Epicurus’s writings have survived, but “judging by its numbers of adherents, Epicureanism was the most successful philosophy in Greek, Hellenistic, and Roman antiquity”, lasting for seven centuries. Much of what we know comes from later writers, such as the Roman Lucretius, as well as from the recovery of fragments of writing on papyri from Herculaneum that were carbonized in 79 AD by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Epicurus developed an Ethics, built on the basis of a theory of knowledge and a physics that greatly influenced modern empirical science. In opposition to Platonic idealism that argued that “sensations were undependable”, Epicurean materialism asserted that “perception through the senses is possible because it expresses an active relation to nature” that was constantly changing.

To understand the world, he expanded on the idea that material reality was made up of atoms (“unsplittables”) and void and that “nothing came from nothing and that nothing being destroyed is reduced to nothing”.

Earlier atomists like Democritus, argued that nature was deterministic and mechanical. Epicurus left room for “some new movement”: his atoms fell to Earth in parallel lines, but “swerved” infinitesimally from their paths at random.

These ideas had a big impact on the enlightenment and modern science: they prefigure natural emergence and extinction, the conservation of matter, gravity, and atomic forces.

Foster shows how the “swerve” had further implications: in Hegelian philosophy, the repulsion implied was “associated with … individual freedom.” For Epicurus, “freedom arose not out of an ideal realm - … like Athena from the head of Zeus – but through contingent struggles associated with human existence itself. In the last instance … what we choose is ‘up to us.’”

Furthermore, “‘the mortality of life [becomes] enjoyable,’ Epicurus wrote, by removing the desire of immortality. ‘Death … is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not.’”

Epicurus’s materialist philosophy of “causal determination, contingency, emergence, and freedom” thus broke the bonds of fate dictated by the Gods of the idealists and the mechanistic determinism of other materialists.

As Marx prepared for his doctoral thesis, Difference between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature, he filled seven notebooks on Epicurus. He noted the influence of Epicurus on natural sciences. But he also noted that for Epicurus, the world of appearance has its being in “a form external to itself, the world of the atom”, where observations of the world were “signs” of what was unobserved. Marx was drawn to this emphasis on complexity, change, contingency, and imminent dialectical contradictions.

This has an echo in Marx’s writings: in Capital Vol 3, during a discussion of capitalist sources of revenue, he comments that “all science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided.”

Marx keyed in on the “swerve” of the atom as leaving room for the possibility of freedom in a causally determined material reality.

Echoes of this can be detected In the Eighteenth Brumaire of Napoleon Bonaparte: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”

The fellow young Hegelian Ludwig Feuerbach critiqued Hegel’s dialectics from a materialist perspective. The ideas of Epicurus were influential in Marx transcending both Epicurus and Feuerbach, as Marx wrote in the Theses on Feuerbach: “The chief defect of all hitherto existing materialism (that of Feuerbach included) is that the thing, reality, sensuousness, is conceived only in the the form of the object of contemplation, but not as sensuous human activity, practice, not subjectively.”

Foster points out that this is a little unfair to Epicurus, whose followers supported one another in equal societies based on friendship and mutual aid – and at times acted en masse to confront tyrannical state formations. The difference for Marx writing during the rise of the capitalist system was the existence of a subject, the working class, that could overthrow the capitalist class through revolutionary struggles: thus he was able to proclaim: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”

Even this echoes a sentiment of Epicurus: “Vain are the words of a philosopher by which no malady of mankind is healed.”

In Marx’s economic and historical works the influence of Epicurus is also evident. Consider this quote from the German Ideology on the foundations of historical materialism: “The first premise of all human history is, of course, the existence of living human individuals. Thus the first fact to be established is the physical organisation of these individuals and their consequent relation to the rest of nature.”

Thus the metabolic interchange between humans and nature, and the dialectic of nature, are the starting point. This is important because the revolutionary wave inspired by the Russian revolution failed to overturn other capitalist states, most importantly Germany. Soviet Russia became isolated and, along with setbacks for revolutionary movements elsewhere, this began to influence the development of Marxist theory.

Starting in the 1920s, Western Marxism, exemplified by the Frankfurt School, denied that there was a dialectic in nature – calling it a deviation of Engels from Marx’s orthodoxy. While Soviet Marxism, after Stalin consolidated control, still officially embraced dialectical materialism, it was distorted so as to become a positivist (i.e. eternally progressive) ideology that became estranged from the material and dialectical reality.

John Bellamy Foster and others that have rediscovered the ecological core to Marxism have developed important tools for dealing with the planetary crises that we now face. These crises are driven by the dynamics of capitalism, a system that subordinates all other considerations to the need to produce profit in order to accumulate more and more capital. In the process, it produces its own gravediggers, the working class that has the potential to overturn the system and “Break the Bonds of Fate.”

Section:

Topics: