Features

You are here

Quebec and York University: The religious accommodation debate

February 3, 2014

The hypocrisy in English Canada about the debate within Quebec over “secularism” has been astounding.

On the one hand, Harper’s government has suddenly become the new-found friend of multicultural and religious tolerance in opposition to Quebec’s Bill 60, or Charter on secularism, which seeks to ban the wearing of religious symbols, including the Muslim headscarf, in public sector workplaces. On the other hand, many progressives in English Canada have viewed the debate in Quebec from a position of superiority. At best, as petty wrangling over Quebec “values” and nationalist identity; at worst, as the “predictable” racism that Quebec nationalism allegedly produces.

But the recent debate over religious accommodation at York University has shown the extent of the confusion that reigns everywhere on this question.

While there can be no doubt about the cynical motives of the governing Parti Québécois (PQ) in introducing its Charter, the racist underpinnings are hardly particular to Quebec. And though there is no doubt that the debate over the Charter has fostered deep racial, religious, and linguistic divisions within Quebec, it is also true that, like at York, many well-meaning Québécois are caught up in a confusing debate that falsely counterposes religious tolerance to women’s equality. That false narrative, which says that all public religious accommodation is the slippery slope to undermining the equality of women and men, has made any reasonable debate about either accommodation or secularism impossible, in Quebec as at York.

Would the debate at York have unfolded differently, had the student requesting accommodation been a woman? The fact that it was a male student requesting not to engage in group work with women allowed it to feed easily into a preexisting narrative that depicts most requests for accommodation as upholding gender inequality. Almost immediately, the specifics of the York case were cast aside. In particular, the fact that the student requesting accommodation quickly withdrew his request was immaterial to what followed.

Not only has the York debate generated a backlash against religious accommodation at universities, it has sparked discussion about whether Ontario, like Quebec, should explore the need for a Charter on secularism. Not everyone involved in the York debate would go so far as to say that the state should legislate against all public religious observance, including the wearing of symbols, but many are saying that institutional practice to accommodate religion should not always be observed. What might have been a local debate became top story on the CBC and other media the week before a new round of hearings on the Quebec Charter was set to begin.

Since the Quebec controversy is part of the immediate context that has shaped the debate at York, it is important to understand what gave rise to it.

Islamophobia and austerity

There is still an ongoing need throughout the West to justify the increasingly complex war on the Arab/Muslim world by linking Islam with the oppression of women, and the scrutiny this has placed on Muslim communities in the West has had a profound impact on domestic politics. But the other key factor is the need to create distractions from austerity measures at home.

There has been a sharp shift in images of Quebec since 2012. For more than a year, students rallied in their hundreds of thousands against tuition hikes, neighbours banged casseroles on street corners against attempts to make their protests illegal, a wide spectrum of the population converged in general anger over economic and environmental policies in what became the “red square” movement, or “Maple Spring.” But the debate over the Charter that started in late August 2013 shifted those images to a society deeply divided from within, suddenly rocked by Islamophobia and even by occasional physical attacks on Muslim women wearing headscarves and vandalism of mosques.

The current PQ minority government came into office on the back of the Maple Spring. They initially kept two key promises: the elimination of the tuition increase that was being resisted, and of the repressive Bill 78 that made protests illegal. However, subsequently, tuition fees were allowed to go up by the rate of inflation. And the PQ also betrayed another election promise, to eliminate the $200 head Health Tax that had been introduced by the Liberals in 2010. And that wasn’t the only backtracking the PQ did on Liberal economic policy: it embraced the Liberals’ “zero-deficit” goal and austerity measures to achieve it. They hiked electricity rates by $75 more per average household, cut $15 million from the $7/day daycares while adding 28,000 new spaces to them, and slashed welfare payments to seasonal workers. And they have upheld the Liberals’ flagship neoliberal project, Plan Nord, the massive plan for resource extraction and exploitation North of the 49th parallel, embraced by mining companies and long the focus of protest for its environmental impact.

The key election promise they did keep was to introduce a law on “secularism.” It is a conscious attempt by the PQ to divert attention, and possibly win a spring election on terms they are comfortable with. The only way the PQ can differentiate themselves from the Liberals right now is with the “secularism” issue. But the Quebec Liberals played the Islamophobia card themselves in 2007 with public hearings on “reasonable accommodation.” That was soon after the last big student strike, which won the repeal of a law the Liberals had already enacted on student grants, and dovetailed with a series of general strikes by unions against Liberal premier Jean Charest. Clearly, the frenzy over religious accommodation that followed was unable to prevent the return of resistance to austerity in 2012.

The PQ doesn’t want to fight an election on the economy (or on its traditional go-to issue, the national question): it wants an election on the Charter, to the point that it has refused to water it down at all to get it passed with the help of other parties. And the ultimate constitutionality of the Charter is equally unimportant, since it is meant to garner votes. The manufactured debate over the Charter has also served to split and weaken the movement that brought the PQ to power. The expectations of that movement were ones the PQ neither sought nor wants to meet. If the Charter becomes law, by the time it is struck down by the courts, the damage will be done.

As for Harper and friends, they too are no doubt pleased to no longer see images of students from coast to coast wearing red squares, and likely glad to see Quebec flags equated once again to a call for exclusion rather than to a symbol of resistance to austerity. And they can continue their double-speak on religion: bashing Quebec, playing to their Christian fundamentalist base, and accusing all those who criticize the state of Israel as anti-Semitic, as well as banning full facial coverage for Muslim women when voting and taking the citizenship oath. It is not hard to figure out which is the one religion not to be accommodated.

Impact of the Charter in Quebec

Not all sentiment in favour of secularism can be reduced to Islamophobia, even in these times of scapegoating. In Quebec there is a long history of very real lack of separation between the Catholic Church and the state, which extended into the school system, hospitals and nearly every aspect of everyday life, which the Quiet Revolution of the sixties challenged.

Nevertheless, linking sentiments against a majority religion with institutional means of repression to denying accommodation for minority religions distorts the debate and prevents all meaningful discussion about how a true secularism could protect freedom of religion for all communities. The only way to allow space for such a discussion is to cut clearly against the tide of Islamophobia and uphold the right to reasonable accommodation in all public spaces.

The debate has worsened preexisting social divisions. Clearly, higher support for the Charter amongst francophones outside of urban centres is in part attributable to the fact that they are unlikely to know anyone personally who would be affected by the Charter. But the very diversity of Montreal meant that all candidates in the municipal elections, which took place as the Charter debate raged, stood against it. The historic first-time election of Mindy Pollack, a Hasidic Jewish woman, occurred in the middle of the debate. Almost immediately after the Charter was introduced, the Montreal municipal government declared plans to use its then-proposed five-year exemption clause to opt out (which has now become a five-year non-renewable transition period). Street demonstrations against the Charter have been largest in Montreal.

While the dominant narrative surrounding the need to ban religious symbols is equality between women and men, it is opposed by a number of important feminists. Françoise David, a key founder of the World March of Women and now elected member of the National Assembly for the left-wing Quebec solidaire, has denounced the Charter as having nothing to do with secularization and everything to do with creating a diversion from policies that have materially worsened women’s lives, policies that were enacted in a National Assembly dominated by a gigantic cross.

“LGBTQ for an inclusive Quebec,” a grouping of Quebec activists and campaigners for LGBTQ rights and for feminism, submitted a brief to the Assembly in opposition to the Charter. They argue that religious accommodation must not be counterposed to liberation for women or for the queer community, and in fact that all minority groups in Quebec should make common cause against discrimination.

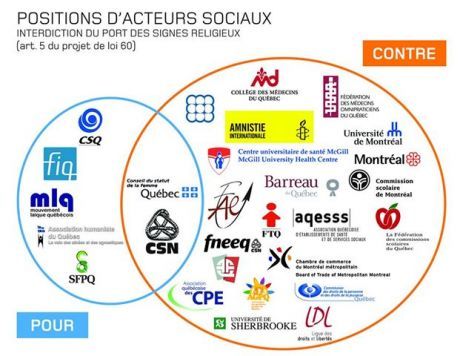

The list of organizations against the Charter, including the Bar Association and many unions, is a long one, as shown in this diagram. Idle No More Quebec is against it as well.

And significantly, many of Quebec’s universities are strongly opposed to the Charter. Sherbrooke rector Luce Samoisette told Le Devoir that the ban on conspicuous symbols could not work in a university, and Robert Proulx, rector of the Université du Québec à Montréal, told Le Devoir that prohibiting employees from wearing such symbols as hijabs, turbans and kippas "is even contrary to universities and the principles of academic freedom on which they are founded."

The debate at York

Academic freedom is raised in opposition to the Charter in Quebec, but at York the academic freedom of Professor J. Paul Grayson, and by extension other professors, was raised as a defence in the refusal to provide religious accommodation, particularly when upheld by a Dean or by an institution. Academic freedom is a hard won right by faculty unions, with a great deal of public acceptance. But the notion that it should be counterposed to other hard-won rights, like religious freedom, is a no-win. As much as the notion that women’s rights must be counterposed to religious accommodation is a no-win. The goal of a truly secular society should be the balancing of rights.

But the narrative that dominated even before the details of the York incident were known, was one that identified religious accommodation intrinsically with discrimination against women. This point is made eloquently in an excellent opinion piece in the Toronto Star by five Canadian Muslim women (“The Misplaced Moral Panic at York University,” Toronto Star, January 24): “We have been warned about slippery slopes apparently ending rapidly and ineluctably in Iranian-style oppression of women. While slippery-slope arguments are excellent for fear-mongering, they often have little basis in legal reality. Religious accommodation is, by definition, an exception to the normal functioning of an institution – not a wholesale transformation of standard practice.”

These women make clear that they are diverse in specific matters of religion but united in concern about the backlash the York incident produced against religious accommodation in general: “We may disagree with the accommodation-seeking student that Islam requires absolute social segregation between men and women (assuming the student is Muslim; his religious affiliation has not been confirmed) – but we defend the right of individuals, including this much-maligned student, to hold their personal religious opinions and to ask the state to accommodate them.”

In the debate, consideration was never given to the fact that certain types of gender segregation are not necessarily equivalent to gender inequality. There is nothing about such a request that would disadvantage the female students in the group. Again, what if the request not to participate in a mixed study group had come from a female student?

But fundamentally, there is a great deal of hypocrisy that underlies the panic over this incident compared to others, particularly when you consider the many recent incidences of sexism on Canadian campuses. We have seen the rise of so-called “men’s rights movements” which call for their own type of anti-feminist segregation in the form of “Men’s Centres,” as a backlash response to campus Women’s Centres. High profile “Men’s rights” speakers promoting rape culture have been allowed onto campuses like the University of Toronto. Last fall, a frosh chant encouraging non-consensual sex at St Mary’s University had to be banned, and just this month St Mary’s is again in the news for its football team sending sexist and hateful tweets. A similar chant about rape at UBC prompted an investigation there in September. And this month, McMaster University suspended an engineering student group, the Redsuits, over a highly sexist and degrading songbook that glorifies rape and violence against women. York University itself has been plagued by an extremely high rate of sexual assault on campus in recent years. Where is the moral panic over all this?

This point is also made forcefully by the five women in the Star: “Islam is not the threat to gender equality in Canada: patriarchy, in all its various manifestations, is. Yet these systemic, structural derogations from equality routinely fail to incite the same type of moral panic induced by the York accommodation case. This suggests that the current hysteria is not simply about the position of women in the university, but contempt for religious minorities.”

Any call for an Ontario Charter on secularism should sound warning bells. Not only would the Quebec Charter do nothing to address the real systemic bases for sexism and inequality of women, but the debate has allowed a small and opportunistic minority to confuse and destabilize broad progressive forces resisting austerity. That same danger must be resisted in Ontario and at York.

Section: