Arts

You are here

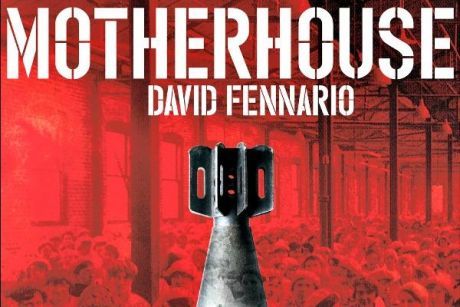

Motherhouse: ground zero for political theatre

February 22, 2014

Motherhouse is designed to be used as a political intervention by the anti-war movement, but it can also hold its own on mainstream stages as a good night-out of entertainment. Who says history lessons on war have to be a downer?

David Fennario’s new play, Motherhouse, which opens at the Centaur Theatre in Montreal on February 25 is a compelling story about working class Quebec women—and one woman, Lillabit, in particular—who worked in munitions plants in WWI. It is also a bold attempt to bring revolutionary politics back into theatre, in the spirit of Bertolt Brecht.

Fennario is considered by many the preeminent working class playwright in Canada. He is an anglo-Montrealer from the suburb of Verdun. He is particularly known for writing the first play that featured both anglophone and francophone working class characters, Balconville, in 1979. He is a life long revolutionary socialist and activist.

The Printemps érable—the fantastic Quebec student strike of 2012 that brought down the Charest Liberals—happened as he was writing this play. He was attending “casseroles” protests in his working class Montreal neighborhood and writing his play about that same neighborhood one hundred years ago during WWI.

Motherhouse is the story of Lillabit, who works in the British Munitions Supply factory making mortar shells. The young men have been sent off to war, many to die in the bloodiest war in history. Many women in working class neighborhoods went to work for the war industry, crammed into loud and unsafe factories, making the weapons of war.

In Lillabit’s factory two francophone women are killed in a factory accident and because their families are not anglophone, receive inferior compensation. Lillabit decides to protest this and finds herself the leader of her co-workers. She gets thrown in jail for her actions and branded a “Bolsheviki.”

It is a profoundly anti-war play intended to counter the glorification of WWI, which is already underway in this year of its centenary. Fennario brings the story of the radicalization of Lillabit to life by interweaving the unique political history of Quebec and war and the ongoing political division of francophone and anglophones, illuminating both the class divide and the national divide within Canada. But, this is no earnest polemic or kitchen sink drama.

Brecht and revolution

Inspired by Brecht’s Marxism and his concept of non-illusionary “epic” theatre, Fennario tells this tale with wit, humour, music and, through Lillabit in particular, the vernacular speech of working class Verdun. He also intertwines two characters representing the recent Quebec student strike, the Carré Rouge, who only speaks French, and a traditional Quebecois fiddler.

Brecht had a profound impact on Western theatre. His writing, his ideas about how to train actors, and his unique approach to staging and production, have been seminal in the development of Western theatre.

These ideas were formed in a volatile historical period in Germany, when it was in the throws of a revolutionary upheaval, inspired by the Russian Revolution, that birthed a republic after WWI.

The main dynamic in this struggle was the role of ordinary workers struggling in mass numbers to throw off an autocratic government. Many of these workers were socialists who held Marxist politics. Brecht embraced these politics—especially the idea that theatre was not something to be consumed by an audience but that it should be an intervention into the politics of the day. “I wanted to take the principle that it was not just a matter of interpreting the world but of changing it, and apply that to theatre,” said Brecht.

Motherhouse as a political intervention

Fennario sees Motherhouse as a revival of the idea that theatre can be a political intervention designed to provoke thought or action and not just something to be consumed. It will surely make people laugh and make some of them uncomfortable.

He has thread politics through the writing, through the environment of rehearsal and the context of performance: incorporating the current political milieu and historical events.

Fennario also sees this play and his method as a challenge to the trend in Canadian theatre training that character is about creating a full illusion. Although this play is very far from “social realism” or naturalism, the actors are encouraged to be non-illusionary to “show what they are showing.”

Fennario has involved political comrades and friends from Verdun in the development of the script and rehearsal process. Outreach has gone to francophone Cegeps, who have booked blocks of tickets, as well as working class anglophones. Échec à la guerre, the anti-war coalition in Montreal that has built massive protests since the 2003 Iraq war, will have a table on opening night.

Political theatre has been making a return in this era of war, austerity and climate chaos. Sadly much of it, although well-intentioned, is naïve and anecdotal. What sets Fennario and Brecht apart is a clear set of political ideas that offers a critical analysis of the world we live in and the intention to insert this into the actual political debate and struggle going on today. This is a revolutionary approach to be welcomed.

For more information visit www.centaurtheatre.com/motherhouse.php

Section: