Features

You are here

How do we fight racism and capitalism?

February 1, 2012

One of the most inspirational chapters in working class history is the story of black workers in Detroit in the 60s and 70s who challenged both their employers and weak-kneed union leaders in the auto industry.

After the Second World War thousands of African-Americans from the South moved north looking for better paying and unionized industrial jobs in Chicago, Detroit and other industrial cities. Many workers in the plants fought in the Second World War and in Vietnam–ostensibly for freedom and democracy—only to return home to racism and low wage jobs.

The Detroit rebellion and workplace organzing

It was these factors that created the conditions for the great Detroit rebellion of July 1967. This saw running battles with the police and mass looting. The National Guard was called in, and along with the racist Detroit Police launched a savage attack on the Black community.

A curfew was imposed, resulting in thousands of black workers unable to get to their jobs. Hastily Ford, GM and Chrysler got the curfew lifted for those who worked in the plants. The fact that the state was prepared to wave the curfew to keep production running showed to many the importance of black labor in the auto industry.

The rebellion produced a group of black radical students looking to connect with black activists inside the auto plants and a group of radical workers from Chrysler—in particular the Dodge main plant and the Hamtramck Assembly plant.

They began to look at ways of winning larger layers of black workers to revolutionary politics and to challenge the complacency of the United Auto Workers (UAW), which refused to systematically fight for black workers seniority rights, or open up the leadership ranks to black workers.

They began to circulate a newspaper called Inner City Voice, which carried articles opposing the war and about conditions in the workplaces and community struggles.

On top of the racism of the employers, were the increasingly horrible conditions inside the plants that raised the anger of black and white workers alike. On top of safety issues, layoffs and unjust terminations, the largest issue was that of the speed up. In the span of one week Chrysler ramped production up from 43 vehicles and hour to over 60. This speed up and the union’s refusal to fight it meant that workers had to take the issue into their own hands.

Wildcat strike and the birth of DRUM

In July 1968, 4,000 workers downed tools at the Chrysler assembly plant, led by activists from the group around the Inner City Voice. The employer responded by firing militants and activists, especially targeting those around the Inner City Voice—including a key leader, General Baker.

The confidence shown by the wildcat spurred the group to launch a new organization and newspaper—Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM)—which began to organize black workers to fight for their rights and assert their power in the workplace and community.

DRUM organized a march of over 300 workers and allies to the Chrysler UAW office, to demand increased hiring into higher level jobs by Chrysleer and for the UAW to stand up for black workers.

Unsatisfied with the union leadership’s response, DRUM called for a wildcat and picketing of the Main Chrysler plant by black workers: almost 3,000 black workers struck. Mistakenly in an attempt to show the power of black workers, DRUM didn’t encourage white workers to join them. Nonetheless the strike sent ripples through Detroit.

The ruling class understood the potent combination of the fight for black liberation being tied to the overall fight of workers, and was terrified that other workers would learn from this and spread the strikes. The Wall Street Journal devoted a major article to it in the immediate aftermath of the wildcats.

DRUM and its leaders came to represent the anger and resentment felt by thousands of black workers across the United States. DRUM wasn’t just a reform caucus in the UAW, it was the spirit of the Detroit rebellion inside the workplace, and it inspired workers in other plants to set up RUMs. Ford workers set up FRUM, Hospital workers had HRUM, and workers at the Eldon Avenue Axle and gear plant formed ELRUM, Cadillac workers CADRUM, Jefferson Assembly Plant JARUM and so on.

These organizations attracted support from activists and even had a movie made about them: Finally Got the News.

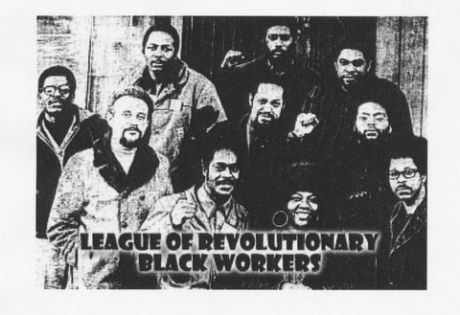

The League of Revolutionary Black Workers

From a spontaneous upsurge of black workers, the need to form an organization to try to knit together the various groups in a more coordinated fashion led to the creation of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW) in June 1969.

The League initiated fundraising campaigns, book clubs to help political education, rallies and demonstrations against attacks on workers and became a political force in the city.

While friendly with groups like the Black Panther Party, the League argued that the strategy of the Panthers in looking to the “brother on the block” as central to winning liberation was mistaken. The League argued that it was the economic power of black workers that was the key for black liberation and the overthrow of capitalism as well.

The League also tried to raise the political understanding of their co-workers, linking the war in Vietnam and US imperialism to the fights on the shop floor. The opening lines of the LRBW’s general statement and policy paper said:

“The League of Revolutionary Black Workers is dedicated to waging a relentless struggle against racism, capitalism and imperialism. We are struggling for the liberation of black people in the confines of the United States as well as to play a major revolutionary role in the liberation of all oppressed people in the world”

The LRBW helped pave the way for a strike wave that rocked the US in the late 60s and early 70s. Postal workers, other Autoworkers in California, and New Jersey truckers all struck. New workplaces also revolted: GM’s new model plant in Lordstown Ohio, built away from the cities and employing mainly young white workers, went out on a wildcat strike that showed the rebelliousness of campuses was spreading into the workplace even more.

Even after the League disbanded after internal troubles, the worksites where it had been strongest continued to have a tradition of militancy. In 1973 workers both white and black staged wildcats strikes that had to withstand both the employer and organized goon squads from the UAW trying to smash their picket lines.

Debates

Unfortunately the League didn’t see the necessity of building a revolutionary organization in the workplace of both black and white workers. This meant that once the League moved beyond the confines of Chrysler—which had the highest percentage of black workers, the RUMs ran into the problem of not being able to relate to the majority of the workers. This sometimes led to actions being called without support from larger numbers of workers, leading to the firing of key militants before building a larger base.

It was this political problem which split he League, between those looking for a way to deepen the presence on the shop floor and those looking to forces outside of the workplace.

Despite not recognizing the necessity of multi-racial organizing, the League’s focus on building resistance in the workplace is a vital lesson for today.

Some on the left continue to argue that power lies in the “community” and amongst the poorest sections of society. They argue that workers are just one of many “groups” in society. The lessons of the League show that if you really want to challenge the system then building a revolutionary organization in the workplace is the most radical thing one can do to threaten the 1%.

Section:

- Log in to post comments